AT THE end of March the free speech and privacy campaigning organisation Open Rights Group published an open letter to Home Secretary Amber Rudd requesting that she extend the consultation into the Investigatory Powers Act.

Despite the fact that the government has now allowed itself to spy on us all ceaselessly, there are still too many people who appear to be apathetic about this enormous breach of human rights.

What’s worse is that the media often joins the government’s call to expand mass surveillance, seemingly forgetting that privacy is so important to their industry.

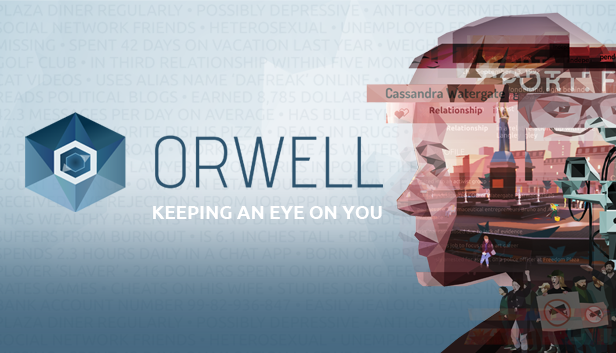

Fortunately, there’s a video game out there showcasing the sheer scale of the freely, and not so freely, available data that we all have on the internet and the truly terrifying depths to which a paranoid/authoritarian government could — and in Britain’s case probably already does — stoop to access it.

Created by Australian indie developers Osmotic, it’s called Orwell — rather an apt name for a simulation game of this kind — and is available on PC and Mac.

Players take on the role of an NSA/ GCHQ-like state surveillance operative for a government known simply as The Party in an fictional country called The Nation.

The game begins with an explosion in the Nation’s capital. As a newly employed operative working from outside the country’s borders, it’s up to you to track down those responsible for the bombing and to ascertain whether there are more attacks planned.

To do this, you use a state-of-theart computer surveillance programme — Orwell — which stores and cross references the data you gather on the suspects and persons of interest.

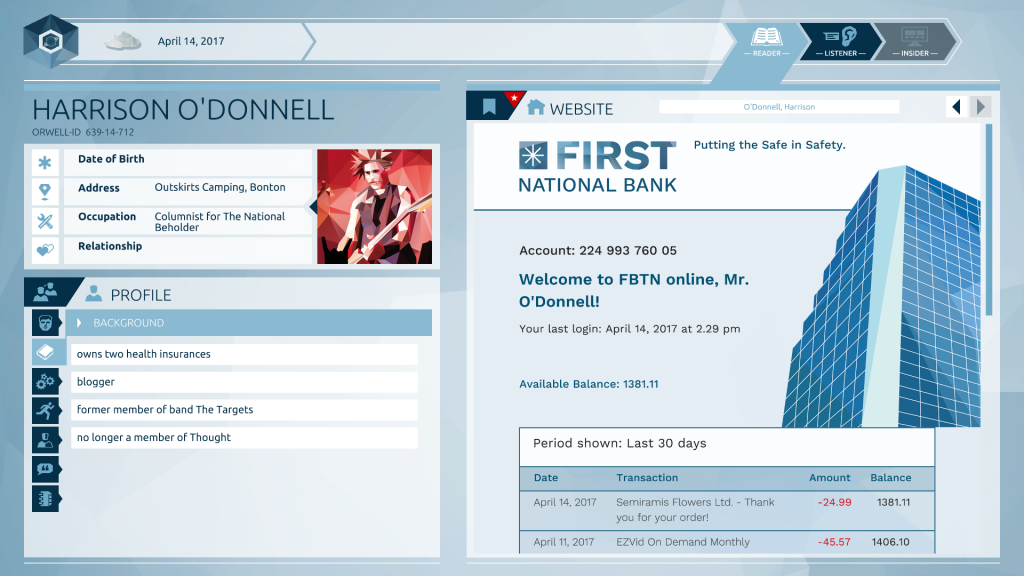

It’s up to you to sift through emails, social media posts, text messages, medical records, online dating profiles and criminal records.

You wouldn’t believe how much information you can glean from a person’s social media feeds. Image skanked from here

Or you can listen in on phone conversations, access bank accounts and hack into phones and computers in order to uncover the names, aliases, locations, motivations, personal connections and political beliefs of the people The Nation believes to be in some way connected to the bombing.

Hacking into a target’s bank account. Image skanked from here

But you aren’t merely taking a passive role. Some of the data you find conflicts with other strands of information and it’s your job to discern which bits are relevant. One of the characters lists her address as Over the Rainbow. Should you drag this information into the Orwell programme, you’ll not only provoke the ire of your employers but also hinder their investigation. But maybe that is your intention.

The ability to frame the way The Nation views certain characters adds an interesting dynamic to the game.

Will you perhaps cast the surveillance target Abraham Goldfels as a rampant communist corrupting the impressionable minds of his university students or as a caring teacher hoping to expand their understanding of the political system under which they are living?

Where the game differs from its obvious inspiration, George Orwell’s 1984, is that The Party is no embodiment of pure evil but a political party quite similar to many Western governments obsessed with “security,” immigration and the economy.

What I found particularly concerning was the fact that the suspects, a bunch of left-wing thinkers concerned with the freedom of expression and the right to private life, are strikingly similar to my siblings, friends, colleagues and readers of this paper.

Orwell is quite possibly one of the most intriguing, unusual and pertinent games I’ve played in a long time.

If you’re at all concerned with online privacy, metadata, the NSA, GCHQ and mass surveillance — but probably more so if you’re not — then you owe it to yourself to experience this game.

A note from the editor-in-chimp: This article originally appeared in the Morning Star, where I work as the deputy features editor.